“History never looks like history when you are living through it.” – John W. Gardner

Our first tale concerns the oldest photograph ever brought to the Heirloom Art Studio, my fine art and restoration studio.

A customer had phoned stating she had a tintype photograph in her possession that had rusted and required some restoration services. At the appointed hour of her appointment, the woman arrived with nothing apparent in her hands. Following introductions, she reached into her purse and produced a plastic diaper bundle which she began to unfold. She grasped the contents between her fingers as if she were dealing cards and thrust the image toward me.

One look at the precious image and I felt faint. My knees buckled as I had her place the piece of metal across my outstretched palm.

I peered down at something I had, until that time, only read about in books. Written descriptions about the earliest photograph produced on small sterling silver plates with mirrored images that flip from positive to negative is inconceivable until one is actually confronted with the real thing.

In my hand I held a piece of history. It wasn’t a tintype, a commonly mislabeled piece of japanned iron dating between 1853 and later. In front of me I held a Daguerreotype, a photographic image first produced in 1839, but not commonly appearing until the mid to late 1840’s.

Forever captured in the delicate silver mirrored tones of black and plum and peering out at me was the soft image of a motherly woman approaching, or already in, her eightieth years. Fast calculations in my head made a quick determination that I was beholding a person from Colonial time. I was holding an image of my customer’s Great-Great Grandmother!

The surface of the sterling plate showed the telltale markings of oxidation, commonly known as tarnish. Where the varnished surface had come into contact with the air tarnish had appeared most prevalently in an oval shape where a brass mat should have been. My customer’s image was not rusted, merely tarnished naturally over time.

Regaining my composure I proceeded to explain to my customer what she had in her possession. The disappointing news was that previous efforts to remove the tarnish through an electrolytic process had just been declared disastrous by the Canadian Conservation Institute in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Previous methods to treat Daguerreotypes were now showing signs of newly created damage. Until further notice there were no approved methods to treat these images except to protect their delicate surface from harm.

I was about to make recommendations when my customer sheepishly admitted she had taken the photograph out of its frame before bringing it to me. Perhaps, she suggested, she should retrieve the framing materials and have me reassemble the works using archival methods. I agreed this would be in the best interest of preserving the image for future years.

A photograph from this time period should have been inside a hinged book-like cover encased by a thin bezel of decorative brass in a sandwich of a decoratively etched brass mat, piece of glass and taped edges intended to keep oxygen from reaching the photographic image on the sterling plate. You’ve all seen these photographic cases in romantic and sentimental movie scenes where characters gaze upon the faces of their loved ones.

I placed the historic image out of harms way and waited for the customer to return with what I expected would be a small handful of framing materials. My second shock of the day came when my customer returned and required assistance getting an over-sized shadow box, glass and framing materials into the Studio and safely placed upon my work table.

She had not only inexpertly disassembled the Daguerreotype’s individual case, thus endangering the photograph’s surface, but had broken into a shadow box that was created and sealed in 1895 and contained an historical essay about items of historical interest.

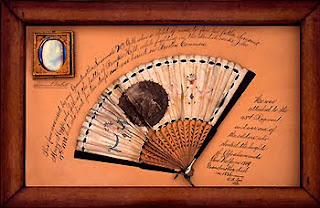

The shadow box contained a paper fan with a circular lithographed print of toga-clad woman lounging in an outdoor scene. On either side of the print was hand painted embellishments of ribbons, bows and flowers.

It was customary for every young woman of culture to possess a fan and to personalize them with hand painted decorations, but the written account and my customer’s story were nothing short of breathtaking. The account written in the framing materials is as follows:

Take a breath!!!!

What my customer did not know was that in times gone by it was popular to pack a picnic lunch, head to a vantage point and……watch the war. The British were known to stop battles in Canada and break for tea with both sides then resume their fighting. War was civilized at least it was until the American Civil War. While crowds sat in buggies and picnicked on the grounds to watch the war, Southern Soldiers broke through the Northern lines and forced their way toward Washington, DC, in a direct path of the spectators. Panic and riot ensued as the civilians desperately tried to return to the safety of their homes and away from the approaching danger. Never again was the public so naive as to consider war a spectator sport.

Things were different, though, in 1775. During the fight for American Independence from Britain our female subject sat and watched her British soldier father fight the Americans and become mortally wounded.

Our tiny photograph of a diminutive woman was of a once living person born in 1766, and only nine years old when she held her dying father’s head in her lap and fanned his face.

History never looks like history when you are living through it, says our quote, yet, here was a recorded account, artifacts and an authentic image of truth and reality. Real people, real lives with a real history.

Using proper archival methods and materials I cleaned the shadow box and its historic contents, repackaged the Daguerreotype and sealed it all in the aged frame to preserve it for the future.

The oldest photograph I had ever handled to date had brought back a small piece of another time and Susannah McGill continues to live in image and memory.